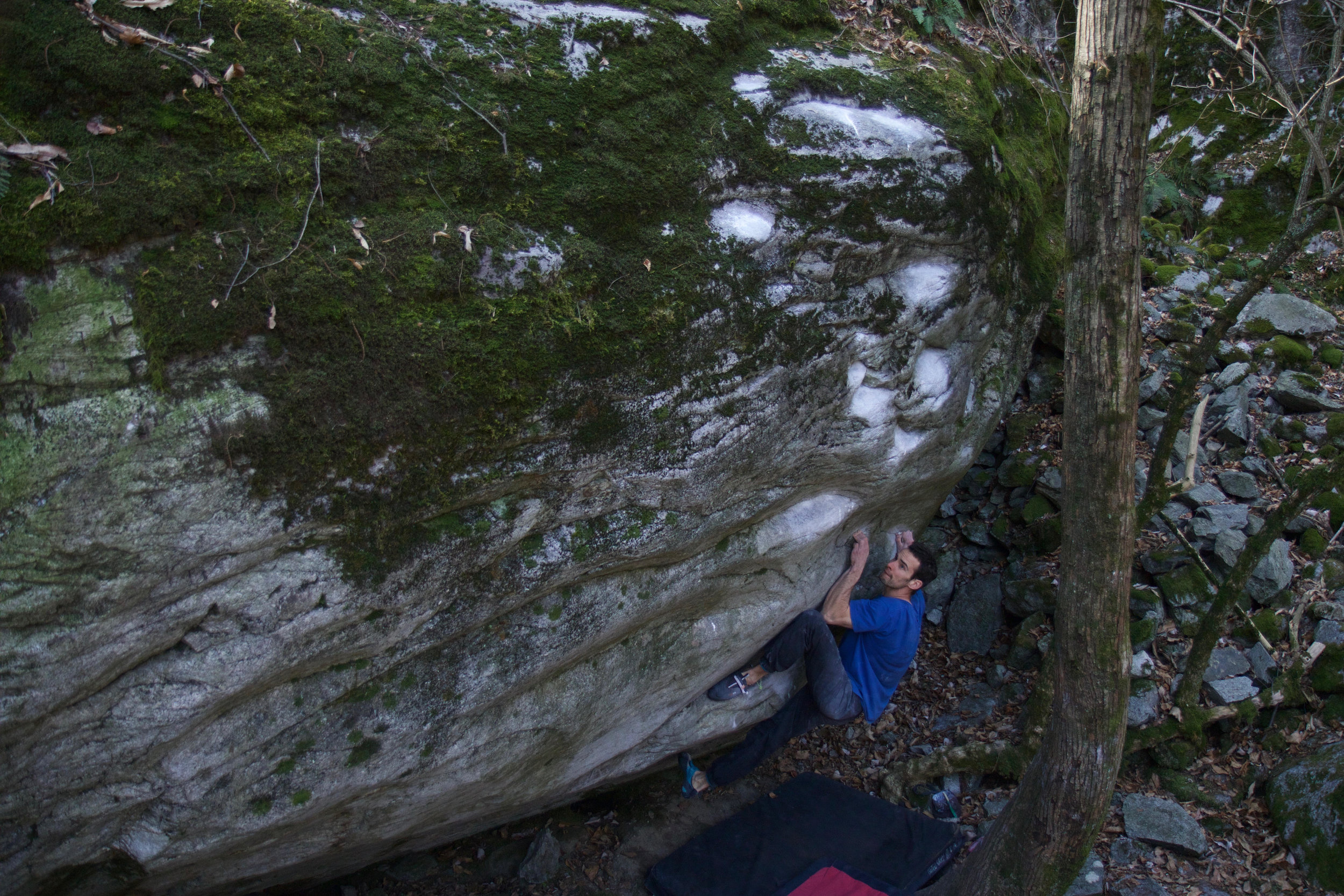

David Mason On Training, Travel and Mind Games

El Corazon 8b (V13) - Rocklands, South Africa. Photo: Jeremy Huckins.

If you pick a bouldering location there is a high chance British climber David Mason has been there, and it's just as likely he walked away with some of the best problems there too. The Sheffield based climber and coach is an avid traveller and over the past decade has picked off some of the world's best lines in the V12 to V14 range across a variety of different rock types.

You're a prolific traveller, when you look back over your trips over the past decade which are the problems around the world that stand out as landmark ascents in your climbing?

Being a climbing geek I love to make lists, I have lists of areas to visit and problems to climb at these areas, the truly special ones make it onto the list. There are criteria to make it onto this list, a climb doesn’t have to meet all of the criteria but it must stand out in at least one area. These are the climbs I remember when I look back. The criteria can be any of the following; historical significance in climbing, the aesthetics of a line, the movement involved, the quality of the rock and probably the most important is the historical significance to me personally and the challenge that that climb has presented to me.

I don’t tend to look back at too many climbs that I have ticked but more forwards at the ones I aspire to climb and places I wish to visit. Plans are hatched, routes are planned all to climb certain pieces of rock that for some reason have made it onto the list. They don’t even have to be especially great! As one climb is erased from the list another five could be added, the seed is planted and at some point I know I will visit an area of the world to climb on that certain problem.

But to answer your question, a few stand out problems for me include; God Module V11 at Horse Pens 40, Western Gold V11 at Dayton Pocket, King Of Limbs Font 8b (V13), Ray Of Light Font 8b (V13) and El Corazon Font 8b (V13) in Rocklands, The Big Show V12 at Flock Hill, On The Beach V13, Cherry Picking V13 and Ammagamma V13 in the Grampians, Superman Font 8b (V13) at Crag X, Paper Birds Font 8A (V12) at The Gop, The Ace Font 8b (V13) at Stanage Plantation, Bewilderness Font 8b+ (V14) at Badger Cove, Permanent Midnight Font 8a+ (V12) in Fionnay, Wing Chun V12 at Ibex, The Hourglass Font 8b (V13) in Västervik, Partage Font 8a+ (V12), l'Apparement Bas Font 8b (V13), Amok Font 8a (V11), l’Angle Parfait Font 7b (V8) and Imothep Font 8a (V11) in Fontainebleau and when it comes to routes Meshuga E9 6c and flashing numerous British routes up to E8, including the infamous Gaia E8 6c at Black Rocks, which is probably one of my proudest achievements.

The list of ones still to climb is much longer!

The Hourglass 8b (V13) - Västervik, Sweden. Taken by Stefan Rasmussen.

That's quite a ticklist of classic lines. Any trip creates a certain pressure and performing under that pressure can be difficult for many climbers at all levels, how do you prepare for a trip? How do you build your training regimes and confidence in the run up to them?

My preparation starts with a goal, without a goal I think I would struggle with motivation both preceding and whilst on the trip. I am not someone who can just turn up and see what takes their fancy; I like to research the area and make sure there is a good balance of mileage to be done, as well as hard climbs that I am motivated to try.

Once I have this goal I tailor my training towards it and try to work specific areas that may help, whilst maintaining a good level of body fitness and condition. The physical aspect of training is not something I struggle with; I love training and working hard to see progression.

For me the key area to succeeding is in the mind; I have always struggled with my head game no matter what sport I am doing. I find it very easy to go down a path of frustration, negative self-talk and, the worst of all, disappointment in myself. Over the last few years I have really tried to put in the time to understand this and find ways to help me deal with these feelings. I am definitely improving but it is a constant battle and I have to remind myself why I go climbing. I love the movement of climbing, the variety and like seeing even the smallest amount of progression; it may only be a foot move or half a hand move but by focussing on these positives I can banish the unhelpful negative thoughts. I think I will always get frustrated when climbing but this is because of how much it means to me and venting this frustration with a shout or scream is, in my opinion, much healthier than keeping it all bottled up.

The biggest part of my prep pre-trip is to climb outside as much as I can whilst maintaining short, intense training sessions. This helps build good skin, allows me to tune up my movement and helps me build confidence. To be honest I just like to try and climb outside as much as I can in conjunction with training all the time!

The Outsider V11 (8a) - Mt Fox, Australia. Photo: Mina Leslie-Wujastyk

The head game is one a lot of climbers can struggle with . When it comes to your training regime how do you divide your time? How does that change when you shift to those short intense sessions in the run up to a trip?

Yeah the head game is a tough area in any sport, and it’s something that I have always struggled with. As a teen I’d smash squash rackets when losing points and now as a climber I definitely have outbursts when falling off. The answer to your question is that I didn’t used to divide my training time very well, it was heavily focussed on physiological gains and improvement of technique. However now I am much more open to ideas and I constantly discuss the power of the head within climbing, especially when coaching. Coaching is great because you are being tasked with improving someone's skill, fitness and mindset; which means constantly trying to grow all of those within yourself as well. I am definitely not quite as on it with reading books and journals as other coaches but I am constantly watching people, gauging their reactions to outcomes and seeing how that affects their performance.

“So many people, and I’m as guilty as the next person at times, are putting in the time to train hard and they think this entitles them to success but it really doesn’t.”

Getting angry doesn’t bother me too much, it is just a release of tension and I think it’s healthy to let that out. Like I said earlier it’s the disappointment that is hard to deal with and that is something I see more and more in climbers. So many people, and I'm as guilty as the next person at times, are putting in the time to train hard and they think this entitles them to success but it really doesn’t. All the hard physical and technical work gets you to a place where things are possible but definitely not a certainty. It’s the head and our approach to the task that brings it altogether.

Meeting my girlfriend (Mina Leslie-Wujastyk) had a big affect on my perception of the head, I used to think "that’s the way it is and I can’t change it". She is very growth mindset orientated and is constantly reading articles and books looking into ways that might help us as athletes, and as people. Long discussions with her over the years have really brought the head to my attention and I will constantly try out new ideas when training or at the boulders. My own mental game is definitely the weak link in my climbing ability, and it’s all down to not liking to fail. Failure is a tough part of any aspect of life but as an athlete we have to embrace failure and be accepting of it because that is what we spend most of our time doing, after all if we were succeeding all the time then we wouldn’t be pushing ourselves hard enough!

I think as I have matured as a person I have found what works for me, and that’s now what I try to practice, although it doesn’t always work. It’s actually the simplest of things too; space and time, often alone, away from whatever I am trying and brushing holds, for some reason I find this very therapeutic!

At the end of the day we climb for fun and if it isn’t fun what’s the point? This is something I definitely have to remind myself of constantly, so that I don’t take it all too seriously. If I go out, with friends or on my own, and try my absolute hardest and come up short then there is nothing else I could have done on that day. Maybe next time it will be different.

That's a great approach to have. How do you structure your work with your athletes and what shapes your approach to coaching?

I suppose that depends on whether they are predominantly rock or competition climbers. The rock climbers I coach, on the whole, are older and much less demanding on my time as I tend to see them once every couple of months, set their training and off they go! I keep in touch with them most weeks to check progress and make corrections where necessary.

The competition climbers tend to be younger and require much more contact time. I work with a close friend, Tom Greenall, and between us we cover their training, weekly squad sessions and monthly individuals to look at aspects particular to them; we are also in contact with most of them on a daily basis! To be honest the training with these guys is the simplest part, it’s all the movement and coordination coaching plus a lot of psych and tactical work to get them prepared for the stresses of competition climbing. We have a few members of the squad that aren’t interested in competition climbing but because they are younger there are still a huge amount of movement skills they need to learn.

Until last year I did this work alone but working with another coach really pushes me too. Tom has very different skills to me and we each bring different attributes to the coaching environment. Areas where I lack enthusiasm he is there to give me a kick up the backside and vice versa. The main thing that drives us both though is working with passionate, driven athletes who expect the same passion, drive and motivation from us. We want to foster a supportive and fun learning environment for them to grow as athletes and people, whilst making sure that they have a say in what they do and listening to their opinions.

The best part of coaching for me is the hands on work; the time you spend with people whether in the wall, at the rocks or at a competition. I love offering ideas and support to allow them to achieve to the fullest of their ability.

Nobody ist der Große 8a (V11) - Chironico, Switzerland. Photo: Thilo Schröter

Do your think the movement aspect of climbing can often be lost when people focus on strength? What advice would you give anyone looking to improve the way they climb?

I definitely think this is possible; one of the biggest problems with modern day training facilities is that people tend to get strong first and this makes learning to climb really difficult, instead of working out efficient technique on a move people will just power their way through.

Alongside strength training it is really important to have a focus on certain techniques. For example two areas that I identified to work on were heel hooks and toeing-in on holds, at the moment I am trying to concentrate on doing some of this every session! I will normally attempt a climb in the easiest way possible for me but once I have done this I make sure to do moves in a specific way. It’s like doing technique drills but on a variety of terrain.

I also think it’s good to climb problems using alternative beta, whether you think this up yourself or are copying another person's method. Another example of this is that I regularly climb with a friend who is much smaller than me, he is incredible at moving on aretes and slabs and so after I have done it my way, often involving lank, I concentrate on trying it with his beta.

Try these things yourself; next time you have a strength or fitness training phase attach a couple of techniques that you struggle with to work on alongside, do a little every session and soon your weaknesses will become strengths. Or at least you’ll not be quite so bad.

With the growth of commercial gyms and the boom in climbing as a sport do you think coaching is something that is in need of professionalization, with a level of knowledge and skill needed perhaps even a qualification? You can often walk into gyms now and find people who have been climbing less than a year coaching.

Yes I think so especially looking into the future and for the development of the sport, however it isn’t that simple. Many coaches have been operating for years without a formal qualification, using their experience and supplementing this with further reading and courses. To ask them to jump through hoops in order to get a qualification that they haven't needed before requires tact and a delicate approach. The British Mountaineering Council/Mountain Training in the UK have two current coaching levels—foundation and development—with a third—performance— being developed. Coaches go on training days and then are assessed like any other national governing body award. The idea of these awards and qualifications are great as in the long run it will stop poor coaching practice but we just need to get the balance right in the change over.

Yosemite Valley in November Photo: David Mason

You've built a portfolio of photography work over the past decade, how has climbing helped you develop that creative side and skill?

I have always liked images and short films showing the landscapes and environments in which sport is participated in; from basketball in down town New York or Chicago, to skateboarding around Dubai, to skiing powder in wooded Japan, football on the streets of Rio or cricket on the streets of Mumbai. Capturing people's motivation, their drive and hard work and the pure pleasure that they experience in all these different natural and man made environments is a real insight to their lives and that really stirs something within me.

When I started to travel more with climbing I decided to invest in a camera and try to take photos and video of the way I see things. I like the landscapes that climbing takes us to and I like seeing unedited footage of someone's battle and the joy it brings them to conquer this. I think that this comes across in both my photos and films. Neither are cutting edge, and they are not supposed to be, they are designed to capture a moment; a try hard grimace, a sense of relief and happiness, or to see the true beauty of where that climb is situated.

For me so much of climbing (and other sports) media is over edited and over sensationalized and this removes the humanity from it. I want to see people having fun, or trying hard or just appreciating what is around them and this can be portrayed in what we capture and how it is edited. Our world is so busy now, so instant, we always want more; bigger, faster, newer but I like simple, I like pen and paper and I like to see what our landscapes or people have to offer.

Editor