Losing The Magic: The Need For Conservation

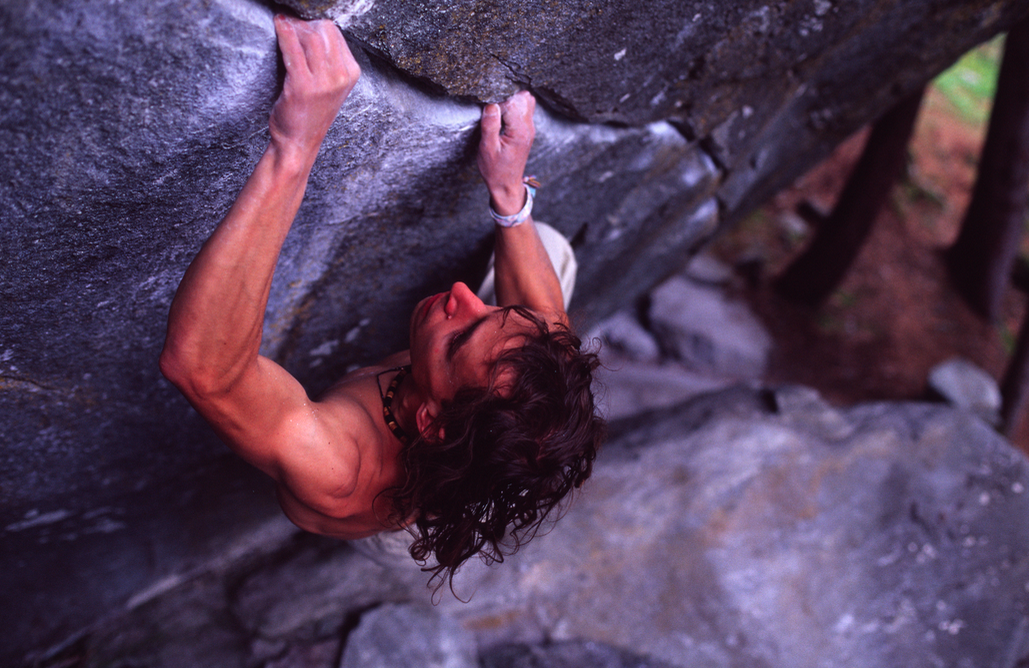

James Turnbull on Jack's Broken Heart Font 8a (V11). Photo: David Mason

Magic Wood; the clue is in the name. A landscape fit for a fantasy, a place where the child in us all can gallivant around until we can gallivant no more. A jumble of silver-flecked granite boulders buried under luminous moss, entwined by gnarled and twisted roots, and enveloped by coniferous forest.

This is how it was on discovery in 1998 by Thomas ‘Steini’ Steinbrugger and his friends, Jack Müller, Bruno, and a little later Bernd Zangerl. Back then there were no bridges to access the huge quantity of unclimbed rock, just a wire across the icy torrent of emerald green water. A special place, as Zangerl puts it 'It was indeed magic for me. Once I crossed the river on the old cable I found myself in a different world. I got all my inspiration from this little place hidden in the mountains, what can I say, I just fell in love.'

After two years and a lot of hard work building landings and cleaning boulders they had climbed around 350 problems; it had become their own private playground where grades were not considered appropriate, just warm-up to sau (very) hard. This playground shot to world bouldering fame with the ascent of New Baseline by Bernd in 2002. Originally graded 8c (V15) it was one of the hardest problems in the world at the time, and people started to pay interest to this previously quiet, isolated Swiss valley. There’s only so long that you can keep a place like this quiet and with the increase in popularity of bouldering, Magic Wood soon became the go-to place in the Northern Hemisphere during the summer months.

Bernd Zangerl, New Base Line Font 8b+ (V14). Photo: Beat Kammerlander

I first visited Magic for a day in 2006, returning for 2 weeks in 2007 and for a further 2 weeks in 2009. It was a beautiful place with so much climbing in such a small space that I thought you could never grow tired of it. Fast-forward to 2018 and it had been nearly a decade since my last visit. I was intrigued by what Magic Wood had to offer a more mature and travelled me and so I decided to return for a short trip to the Avers Valley. Would the area still be as captivating as ever or had it become a victim of it’s own popularity in this boom period for bouldering?

I am going to cut a long story short and not keep you in suspense; in fact I imagine you know where this is headed already. To put it bluntly I was appalled by what our sport had done to this once beautiful area, and how we as climbers had seemingly just let it happen. Speaking to Bernd now it is clear he has similar feelings and is bitter sweet about what has occurred since the area was opened. 'It makes me happy when I see the forest and when I see that people are having fun but it also makes me really sad (to see the changes within the forest) and I feel partly responsible for that.'

This piece has not been written to blame or judge anyone; I was just so shocked that I thought it would be useful to bring these matters to the attention of others and create a brainstorm of ideas for what could be done to save other areas that could go the way of Magic in the future.

What was I so shocked to see in Magic?

- Rock and holds that had become so caked in chalk and rubber that grip and texture was a thing of the past.

- Paths that had morphed into highways and new paths where once there had been vegetation.

- Tree roots so exposed and polished from foot fall that it’s amazing the tree is still alive, or that it hadn’t been sued for causing someone an injury!

- A good amount of litter, toilet paper and cigarette butts around the areas.

Bernd Zangerl on Tintenfischalarm 8a+ (V12). Photo: Beat Kammerlander

With these in mind, what simple measures as climbers visiting these areas can we do to help keep it as close to how nature intended as possible and maintain a pleasant environment for others to be in?

- Don’t climb on wet rock.

- Take litter home with us but also pick up other litter that we see.

- Brush and clean holds during and after use.

- Brush tick marks off, whether they are yours or not.

- Pick up and carry crash pads rather than dragging them along the floor between problems.

- Make sure our climbing shoes are clean before getting on the rock.

- Limit the amount of noise we make, however enthusiastic we are being.

- Stick to marked or obvious paths and not just walking wherever is easiest.

- Bury human waste and take toilet paper home, don’t use it or burn it rather than leaving it to mark where we have defecated.

- And please don’t play music at the crag; it’s really disrespectful to others in the area.

These are small contributions that each of us can make to an area we visit but what urgently needs to be addressed is the wider education of new, and experienced climbers, in how to behave when at a climbing area. This, I feel, needs to come from brands, professional athletes and climbing walls/gyms around the world. With so many people being exposed to climbing on a daily basis the numbers that participate is only going to grow and many more areas will go the way of Magic Wood. Rocklands is a great example of this, and although there is huge potential for growth of new areas in the Cedarberg we must still treat it all with the greatest respect. Even the gritstone in the Peak District, my local climbing area, took a battering this winter with people caking damp and wet rock with chalk in order to climb.

The Access Fund in the US seem to do great work in trying to spread the word on how we should all behave when out climbing, UKClimbing have also had a big push this winter here in Britain and Black Diamond have initiatives like Chasin’ the Rubbish in Fontainebleau that climbers such as Nalle Hukkataival, Fred Nicole and Jacky Godoffe have huge involvement with. I’d like to see much more like this and a push from climbing gyms to help inform new climbers coming through their doors on how to behave when, or if, they decide to go out climbing on rock.

David Mason on Electroboogie 8a V11. Photo: James Turnbull

Perhaps a more drastic measure, and one that I have spoken to bouldering legend Bernd Zangerl about, would be to close an area or sectors of an area for a season to allow them to recover from the constant onslaught, rather like a farmer leaves a field to fallow for a period of time to restore its fertility. Most areas around the world have a relatively short peak season and so just a few months respite would actually give an area a much longer period for vegetation to regrow and rain to do it’s best to clean the rock. This coupled with an organized clean up at the beginning of this ‘fallow’ period may really help rejuvenate and allow nature to flourish once again. I understand there would be economic repercussions to the closure of an area and I am not sure it would be possible everywhere, or even anywhere, but it would allow an area to breathe a little.

“If we all do a small thing each time we are out... then we can start to create a much more sustainable future for climbing in the great outdoors.”

Hueco Tanks is an area where, at first, having to pay to climb or having restricted access appalled climbers, but if you speak to Tanks regulars, guides or park officials they really feel it has made a difference to the park and the longevity of climbing there. This approach would not work everywhere but as our sport grows a balance between nature, culture, history and pleasure must be struck to keep everything and everyone happy.

My trip to Magic Wood served as a wake up call to what we are doing to these areas. I am not a saint, I use tick marks, I have stashed pads and I travel more than most to pursue what is essentially a selfish life. But over the past few years I have become more and more aware of our impact upon our environment and I want to start to do something about it and to educate others too.

Joe Lawson on Protektor 7a+ (V7). Photo: David Mason

Taking a stand and helping to create and maintain a more sustainable approach to climbing in the outdoors is a shared responsibility in our community. If we all do a small thing each time we are out, whilst brands and gyms attack this from a wider standpoint, then we can start to create a much more sustainable future for climbing in the great outdoors. I was so saddened and disappointed to see what had happened to Magic Wood and from speaking to others I know they feel the same, whether they are locals or just visiting for the first time. One of the original developers Steini no longer climbs but perhaps we can all take something from his approach. 'I stayed in nature for my whole life, enjoying the silence and spirit of climbing with respect for the environment I was in.'

Climber, coach photographer based in Sheffield